It’s time for some memories from old days…a few years back, from, probably, the closest petroleum geologists get to pilgrimage: Kimmeridge Bay, a troll’s stone throw east of Weymouth. Still on the English Channel Coast, we jump a bit down again, to the Upper-Upper Jurassic. Kimmeridge Bay is home to the shale above all shales, the one shale to feed them all – all the the oil fields, that is. Its dark, dirty shale is the source rock for most of the oil in the North Sea.

Kimmeridge Bay on a sunny day and at low tide. Note the lighter, hard layers; one at the top of the cliff to the right, and another that makes the floor of the beach. These are sandstone layers, a nice contrast to the dark shale. They show how the whole section dips gently, so it is possible to walk up and down through the layers along the beach.

…and a not so sunny day, but with nice, arch-British rolling countryside behind. Note how the shale layers alternate, some are very organic-rich, darker than a black cat in a coal mine, while some lighter grey layers have less organic matter, and show that there were cycles between the most anoxic periods.

In the Upper Jurassic, the North Sea was a shallow sea within a rift zone. The spasms that heralded the opening of the Atlantic Ocean here had been going on for quite some million years, and created a seaway surrounded by steep faults. (The rift later jumped westwards and opened the Atlantic Ocean in its present position. Had it continued in the North Sea, the British Islands might have ended up in splendid isolation somewhere in the Atlantic Ocean, far from the annoying EU).

When in the Jurassic, visit Lyme Regis, the cradle of paleontology!

During the Kimmeridgian – yes, that period on the time scale got its name from the bay – the basin-bounding faults had created some quite isolated basins, with little water circulation. Low circulation means little oxygen at the bottom, which in turn means that organic matter sinking to the bottom does not rot, but is preserved and covered by more sediment. Most of this organic matter is dead algae. No, oil doesn’t come from dead dinosaurs. There were not enough dinosaurs, but zillions of algae, probably turning the sea surface into green slime for long times.

Bonus for structural geology nerds like me: beautiful fracture sets in the harder sandstone floor of the beach. Note how the fractures mainly strike in two directions in the image; from upper right to lower left, and from top to bottom. The acute angle between them show that the stress that created them was oriented approximately perpencicular to the shore line, along the biscting angle of the two fracture sets.

Add time, burial and heat down in the deep North Sea basins, and the algae break down to oil. Add more burial and heat, and the oil breaks down to gas. In Kimmeridge bay, the rock hasn’t been buried enough to do the final cracking to oil, but parts of it is actually so rich that it burns if put onto a fire!

And – Kimmeridge Bay is a great place for fossil hunting!

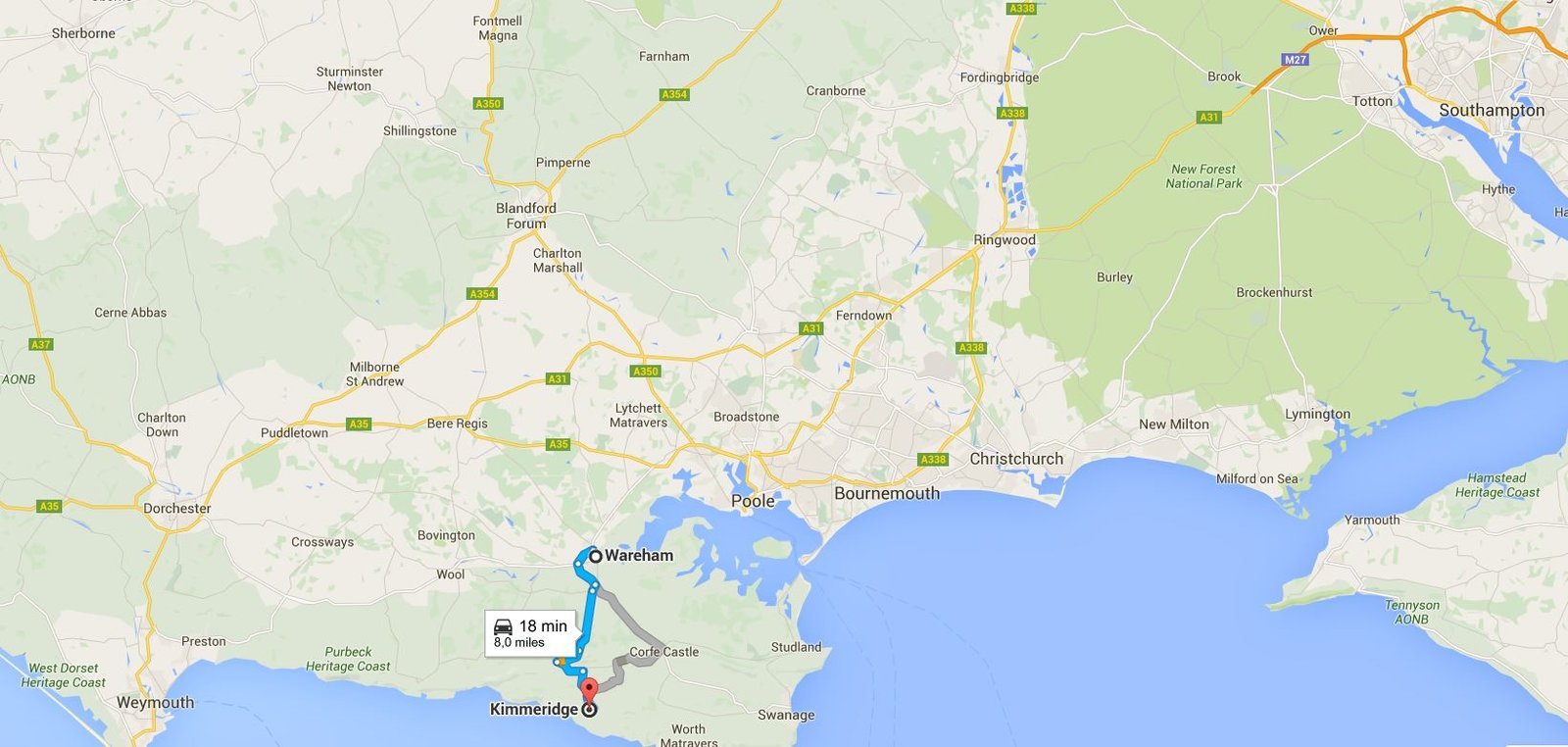

How to get there

By train: Southwest Trains from London Waterloo, the nearest station to Kimmeridge is Wareham, 8 miles from Kimmeridge Bay.

By car: Folow M27, then A31 from Southampton, and around Bornemouth. Then, A350, onto A35 and then A351 to Wareham. From Stoborough, Grange Road towards Kimmeridge.

Hi KARSTEN

Just a note, while reading your great blog, there is no sandstone in the section at Kimmeridge Bay. The image you have labelled up for the seen fracture sets is dolostone. Secondary cemented shale with dolomite. The pale yellow colouring is a weathering feature.

The conversion is a volume increasing reaction and is why these hard ledges have an undulating nature to them.

Cheers Andrew