It looks like some kind of giant, grey underground worm with teeth radiating in its mouth. A sand worm from Dune, which happened to dig its tunnel out of a mountain on Tenerife, and like a troll, froze to stone in the sun.

In reality it was a thick, viscous lava flow, like a flowing, hot chocolate cake dough, which stopped in its track and cooled from the inside out. The front broke off and revealed the teeth.

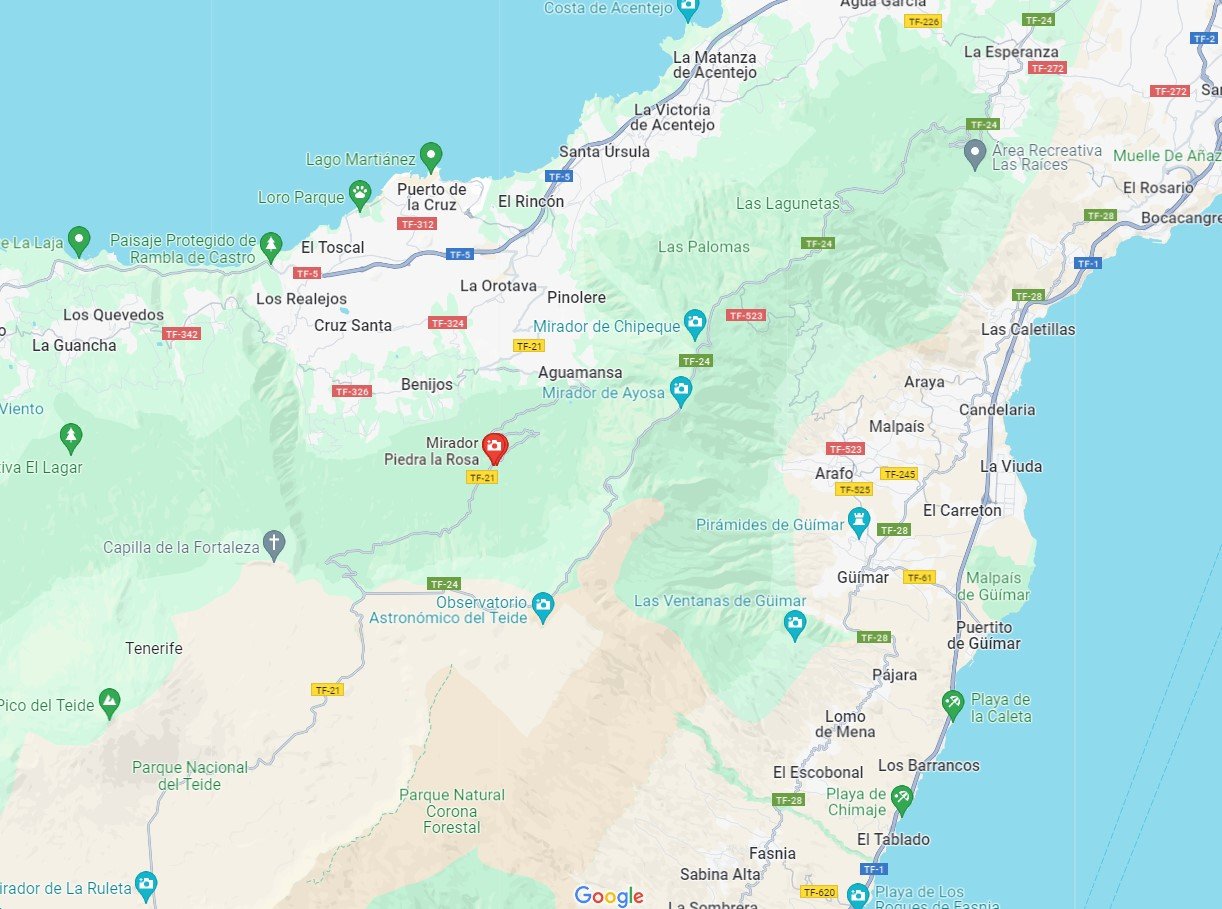

You find it at Mirador Piedra la Rosa on the north flank of El Teide. The name means “the rock rose viewpoint”, and the lava worm does in fact also look a bit like a flower with the petals opened. Just nearby is a lookout with a view towards the beautiful Orotava valley (at least in between the tall pine trees).

Basalt columns like the Rock Rose form when a flow of lava cools. Rocks shrink when they cool, and the resulting void creates fractures. If the lava is a bit heterogeneous and flow on the surface, like a chocolate cake dough being poured into a large oven pan – mandatory for kid birthday parties in Norway – it shrinks downwards, with lateral (geologese for sideways) shrinking making irregular cracks.

But if the cooling is fast and evenly distributed, going from the top and downwards, it will create an even lateral shrinking, making even-sided columns.

Why six sides?

The more sides that form fractures, the more efficient is the release of stress in the shrinking rock, and six sides is the most that are geometrically possible. Three or four sides is geometrically possible, and such columns do sometimes happen. On the other hand, five, seven, eight or more-sided columns are not geometrically possible: Try to cover a floor with five, seven, eight sided tiles: it is impossible to make them fit. Six sides make the goldilocks shape. Honeycombs have six sides for basically the same reason, the most sides and thus the “roundest” and most efficient hole that can be made with planar walls.

In the real, messy world of rocks, the shrinking is often uneven, and columns get irregular shapes. But where the shrinking is even, six sides are the geometric rule.

Where a horizontal lava flow cools fast, the columns become vertical; vertically the lava can just shrink down, but laterally, the small void left by shrinking is taken up by the six-sided fractures. The Giant’s Causeway in North Ireland is the most famous example, and on this blog, I have shown similar columns from Scotland.

Lava on its way to the surface may follow not only the main vent of the volcano, but commonly go through sets of fractures and faults that pierce the crust, creating steep veins, dikes in geologese. When this lava cools, it also fractures, sometimes making nice six-sided columns, but the fractures and columns are perpendicular to the walls. This happens because the dike can always shrink and become slightly thinner, but along the dike it can happen only by fracturing.

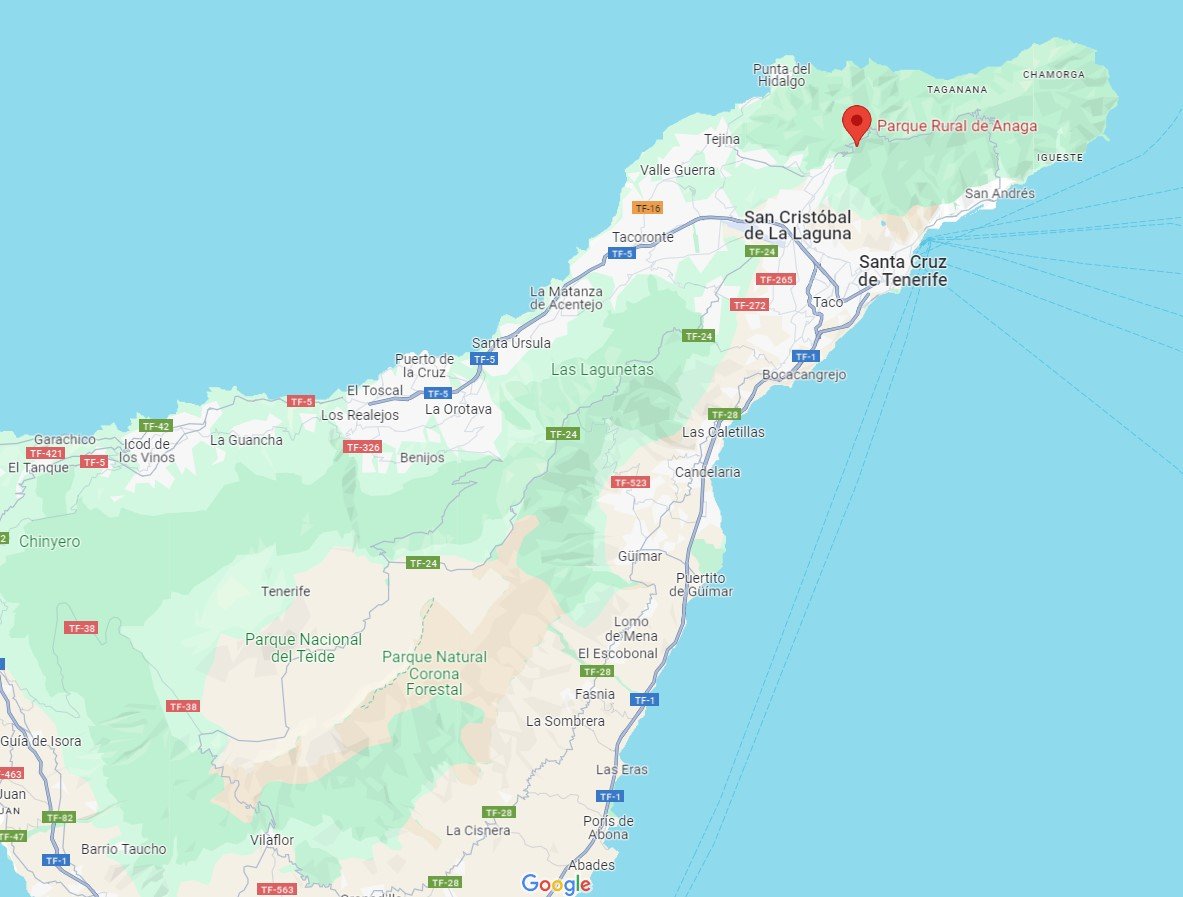

The images here are from the Anaga Peninsula, the northernmost part of Tenerife. Here, the rocks are eroded down to the oldest rocks on the island, tuffs and volcanic ashes. These are criss-cross-cut by dikes that led lava to younger volcanoes, and the dikes all have more or less well-developed columns.

How to get there

The Rock Rose is situated on the north side of Tenerife, on road TF-21, down from the Canadas caldera towards the Orotava valley. It is just beside the road.

The dikes in the images are from the Anaga peninsula, a long tip of the island towards the northeast, incised by steep valleys. I admit, I have forgotten exactly where the images are taken, but the peninsula is crisscrossed by dikes almost everywhere.

Tenerife is a major sun-seeker holiday destination, and can be reached from almost every city in Europe, mainly by charter or low-cost flights. The best way to get around is to rent a car. I recommend to rent only the second- smallest car, because some horsepower is good to climb the steep roads. Keep in mind that the roads around the high Teide sometimes are slippery due to frost during the winter.