1:55 AM, January 23rd 1973:

– Honey, there is a volcano in our backyard!

– Yeah, right, Steingrimur, get back to sleep now!

I do not know if this talk ever took place. But it could have, and half of Iceland is named Steingrimur. (The other half is named Harpa).

Another version is that Steingrimur woke up that night and wondered if someone had too many leftovers from the New Year fireworks.

But that night, January 23rd 1973, a volcano did suddently erupt just one kilometre from the centre of the little town on Heimaey island. A fissure opened, spitting out ash and lava, and within a few hours it had became two kilometers long.

Luckily, storms in the days before had kept the whole fishing fleet at harbour, and the eruption did not reach the airport. Within a few hours, the whole population was evacuated.

It was the first volcanic eruption on Heimaey in five thousand years. But, only ten years earlier, a submarine eruption had created a new island, Surtsey south of Heimaey. It was named after Surt, the Norse god of fire, and he was obviously not finished with his work in the Vestmannaeyjar archipelago. He worked on through the spring, and soon concentrated his pouring out of lava on one vent, flowing towards the outer harbour.

Vestmannaeyjar harvests around one third of the fish landed on Iceland. In a heroic effort that would make for a good Hollywood movie, a ship pumped seawater onto the viscous lava front. Then, pipes were laid out onto the hot lava, barely solid on top and foggy by steam. More than a ton of water per second was pumped onto the slow glacier of lava.

It worked. When the eruption stared ceasing in April and finally ended in July, Heimaey had grown one-fifth in size, and the new land actually improved protection from the sea. The price paid was four hundred houses buried.

Icelanders may swear the hassles from their restless underground, but they are even quicker to take advantage of them: In only one year, the first house was connected to a new geothermal heating system, with pipes into the hot lava deposits. The buried town, partly dug out, has became a tourist attraction, a Pompeii of 1973.

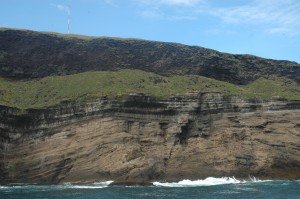

The brand new volcano, Eldfell (Fire mountain) is a 220 meter tall cone, looking slighly down onto the older sibling next door, Helgafell (the holy mountain). Helgafell is old of age, erosion has taken its duty on her face through thousands of years, but her beauty preserved by the cover of moss and grass on the lower flanks. Eldfell is the brown and fresh youngster, a fresh face, but with a barren, immature desert, a teenage Mordor from the Lord of the Rings.

Today, forty years later, puffs of steam still come from holes in the ground, lined white gypsum crystals. On top, fumaroles with yellow crusts of sulphur, glittering from thousands of micro-crystals, remind us that the volcano youngster, only a year older than me, has not entirely rested.

From the top, Heimaey is like a modern painting with strong colours: The rusty brown of the Eldfjell cone. The black of the young lava. The intense green of the grass on the older soil. And, in the background, the blue-gray sea. Next stop southwards: the Canary Islands, then Antarctica.

Eldfell is a place to just sit down, to look over the sea, to allow time to stop for a while. A place just to appreciate this fantastic planet.

My favourite picture from Heimaey: The brown Eldfell cone, the black young lava, the green older soil – and the blue sea in the background.

Puffins are the “national bird” on Vestmanneyjar, so it is only natural that “puffin bills” give directions to both the current and the buried town.

Pingback: The Day the Mountain of Fire Was Born | Steph's Random Facts·

Pingback: Birth of a Volcano: 41 Years Later, This Icelandic Town Still Thrives – Yahoo Travel | Ultimate News Update·