In between writing the reports from Svalbard, I had to do a business trip to Scotland, still part of the Fairly United Queendom. Then, I enjoyed a couple of days in Edinburgh, Scotland’s Capital, eating the national dish Haggis, with ‘neeps and ‘tatties, and exploring its magnificent castle and streets with extremely British ornamented rock buildings. Edinburgh looks like Hogwarts’ City.

Edinburgh, the city of magnificent stone buildings, populated by young wizards and ghosts of famous geologists.

View from Edinburgh Castle , with the walls of the Salisbury Crags in the background.

But a geologist always looks at rocks, not only those that make up the buildings. You know you are a rock nerd when the minerals in the Scottish Crown Jewels are even more interesting than the halls full of memorabilia from wars around the Empire. And the most notable rocks in Edinburgh are the big ones below the castle itself, and the even bigger hill Arthur’s Seat, just outside the town.

Admittedly I had cheated and checked out their origin on The Internet up front, but the origin of the Edinburgh castle hill is obvious as soon as you enter its magnifcent gates (or just grit your nose towards the foot of hill). It is a dark, magmatic rock, with texture quite like a paleo-Haggis. Ediburgh castle resides on the pipe of an ancient volcano.

Edinburgh Castle, perched on top of the Early Carboniferous volcanic plug. Hard and steep, the old volcano makes it a natural place for defense works.

During the Early Carboniferous, ca 340 million years ago, volcanic magma found its way up the crust in what today is Midland Valley, the gentle sag where Edinburgh and Glasgow lies, and created volcanoes. Today, numerous remnants of them remain as bumps in the landscape, after being first buried during later times, tilted by tectonics and then uncoverded by the erosion of ice age glaciers.

Arthur’s Seat is one of the larger, and I had to conquer it. A daunting… eh… half-hour walk from the city centre, and then another half-hour to the summit, it gives a beautiful view of Edinburgh, the Firth of Forth and the snow-draped highlands around.

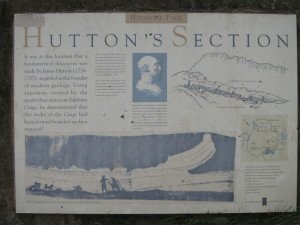

Arthur’s Seat possibly has its name from the legendary king with the round table, routines and chorus scenes and all that. Geology’s Co-Craddle (in addition to Siccar Point) would be an appropriate name too. It was one of the crucial places for James Hutton, called the father of modern geology, to realise the vast age of the Earth. Let’s go for a walk in his trail.

Looking from the city, the most prominent feature of Arthur’s Seat is a steep wall, the Salisbury Crags cliff. It is a huge dike intrusion, which spread out from the centre of the volcano and into a weak layer in the sandstones around, as the magma worked its way upwards. It stands outs as a cliff because it is much harder than the sandstone. Vertical fractures that penetrate would make it a great place for climbing (thanks to the sign that got my climber-attention, by saying climbing was illegal).

Beneath the Crag is a red sandstone. A smaller igneous vein has forced its way into the sandstone, broken it up into fragments and folds. This was the place where James Hutton got the final proof that volcanic rocks forced their way up into the sediments above, and thus made up a large part of the Earth’s crust. Today, the idea seems obvious, given that we observe volcanoes, but in the 18th century, many geologists thought that rocks formed by precipitation on the bottom of oceans.

Yours truly as scale, in front of Hutton’s Section. A vein of volcanic rock, has forced its way into the sandstone. The steep cliffs of the Salisbury Crags in the background.

Close up of Hutton’s Section; the homogenous volcanic vein in the upper part of the image, has shoveled its way into the sandstone below, and bent the sediment layers.

Hutton’s Section has changed since he was there, due to quarrying. But the geological point is still excellently displayed.

After some contemplation on the long time spans of the Earth and earth sciences, I rounded the crag face and start ascending Arthur himself. On the way up, one can see that the rear surface of the crags follow the top of the intrusion, an even, gently dipping surface. Sediments that once were on top of it are gone, but the hard crags remain. The mountainsides of the Seat – where it peeks through all the botany – consists of all kinds of volcanic hodgepodge that can make up a volcanic cone. More on that later. But the barren top is what a volcanic plug should be: The fairly homogenous, dark intrusive Haggis-rock.

Salisbury Crags from the rear; note how the terrain follows the top of the hard igneous dike, but the softer sediments that once were above are gone by erosion.

Top of Arthur’s Seat, with the hard volcanic rocks in the foreground, and view towards Firth of Forth and Edinburgh’s harbour.

During its active period, the volcano was higher, probably with a proper crater like volcanoes today, and slopes built up by scree from the eruption products. It is the feeder pipe of the old volcano that constitutes its top today, and a closer look at the slopes reveal that they are made of a hodgepodge of intrusive branches from the main pipe, conglomerates and rocks of various sizes.

Why is Edinburgh castle not on the taller and bigger Arthur’s seat? Possibly because the seat is bigger, with fairly gentle slopes to all sides. Castle rock is steep to three sides, and gentle only on one side towards The home-of-tourist-traps Royal Mile, and thus easier to defend. However, remnants of ancient defense works also exist on the Seat.

It is tempting to think of the volcanoes as the origin of Edinburgh: Volcano rock hill, castle on top, city around. Edinburgh’s status as capital of Scotland is certainly closely tied to the castle on the volcano hill. It has been fought over by Englishmen vs Scots, and various branches of Christian faith through the ages, and it protected the city (or attracted attackers). Historians are not certain if a fortress of some kind came first, and the village grew up around it, or if a village once emerged in the lowland on the coast, and then sought a place for a castle of refuge. In any case, volcanism around 340 million years ago had quite some impact of Scottish history.