It is a grey day in the mountains. White fog is everywhere, and embraces the pine trees on the steep hills. Drizzle in the air, just enough to make me wipe the lens every half minute. My feet slip on the path.

Then the fog lightens. Slowly, just enough to reveal a blue sky above and – is it an enormous totem pole?

As the fog gradually gives way to the blue, Roque Nublo emerges as a huge monolite, a hundred meters tall finger pointing towards the sky. And its base is a mountain top with view all the way to the sea.

Is this really Gran Canaria? The place otherwise famous for cheap cerveza, fatty food at tourist traps, all-inclusive and skin burns that look like the surface of Jupiter’s moon Io?

Yes. This is the story of the other Gran Canaria.

An island that has been called a continent in miniature, with deserts, lush forests, steep valleys and even steeper cliffs. An island of pittoresque villages in the mountains, and steep, mighty valleys.

Gran Canaria is also a volcanic goodie bag for geology tourists. Join me on a trip to the great Canary, for lava, colourful ashes and a landscape that could make even a fjord-spoiled Norwegian jealous.

Gran Canaria is built by volcanoes, where eruptions have piled up lava and ash to make an island; first from around 14 to 9 million years ago, and then from around five million years nearly to today. It is in the middle of the string of volcanic islands that make up the Canaries.

El Hierro and La Palma in the southwest are the younger of the Canaries, and then the islands become overall older towards the northeast. However, the volcanism has gone a bit back and forth; and Lanzarote at the eastern end experienced one of the longest eruption series in historical times, the Timanfaya fires from 1731 to 1736.

In fact, the Canaries basically has the same origin as Hawaii: They are both the result of a crustal plate gliding over a hot spot, where a plume of hot magma rises from the deep and creates volcanoes. As the crustal plate glides by, new volcanoes steadily form above, and then erode down as time and tectonic plate goes by.

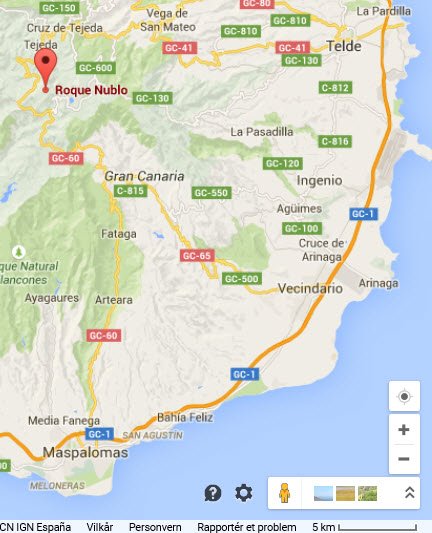

Gran Canaria with the red dot at Roque Nublo; in the middle of the volcanic Canaries chain. Volcanism today takes place mostly in the western part: La Palma had its last eruption in 1970, and in 2012, there were submarine eruptions near El Hierro the southwesternmost island. The coast of Africa, wth Morocco and West Sahara, to the east.

Roque Nublo looks as if a giant Obelix had walked by, left a hundred meters tall bauta stone and forgotten it. I walk to the foot of this pinnacle, where I become small as an ant besides a garden rock. A flat plane runs through the base, as if giant Obelix cut it loose, messed up the surface a bit ad put it back. Contrary to the roques I previously saw on La Gomera, Nublo is actually not an old volcano plug. The brown rock is mainly ash and tuff, fine grained material spit out as heavy clouds, rather than floating lava. Through time, the sticky grains welded together to a hard cement.

It is the last remnant from a time when the mountain was bigger and taller, before erosion’s merciless forces tore it down and flushed it to the ocean. The Roque is the last rock standing, as a big finger towards erosion: “fuck you, erosion, you don’t get me!”

To which erosion, casually, replies: “pffft, just you wait, I’ll get you in the end, even if it takes a few million years!” A million years may sound a long time to us, but is a mere blink on the geological time scale, and just a fraction of the age of Gran Canaria. But, in a few million years, it will likely look more like the flat, torn down deserts of Lanzarote and Fuerteventura.

The cut at Roque Nublo’s base is actually a glide zone: The tall mountain probably became so high that it slid back under its own weight, and in the glide zone – detachment in geo-speak – we can see colourful bands, drops, whirls, of ash, twisted and dragged out to artistic shapes.

The fog starts to return. Roque Nublo’s top once again is draped in white. I start walking back, down into the forest. But, just before the trees close around me, I see another roque, in a window in the white shroud. It has the shape of a lady standing, praying, almost out of this world. To a faithful, it would probably feel like a reminder of virgin Mary or a saint, to me it could be Mother Nature herself.

I manage a few shots before she again disappears in the white. Raindrops start falling on my head again and I head back for the car.

—

How to get to Roque Nublo:

Gran Canaria is a major tourist destination, and served by a zillion airlines; charter, low-fare and good-old ones. From Norway, both SAS and Norwegian flies almost daily. Car rental is inexpensive, down to less than 100€ per day. Obviosly, both plane fares and car prices depend on season.

Roque Nublo is almost at the hub of the round island of Gran Canaria, where steep valleys radiate out as spokes. The roads to the rouqe may look long and vinding on a map, but are really just vinding.

Driving distance from Gran Canaria airport is around 40 km, and takes just below an hour on the mountain roads. Follow GC-1 southwards from the airport (or from Las Palmas), take GC-120 at Carrizal and then GC-130 and GC-600 further to the parking spot, Aparcamiento de la Degollada de La Goleta. From there it is a less than 2 km walk on the paths to Roque Nublo. Make sure to use good footwear and keep something windproof.

From Maspalomas or Playa del Ingles, GC-60 northwards inot the mountains, then GC-600 to the parking place. Driving distance and time is around the same; 40 km and one hour.

Pingback: Gran Canaria: The Miniature Continent | Adventures in geology - Karsten Eig·