I made you click, didn’t I? But it is not that kind of heat, or that other kind. It could be the hot summer days in Tuscany, when the crop fields turn from ripe yellow to almost brown, and people hide inside, taking siesta because they have to.

But, since this is a geology blog, the heat in the headline is the one from deep in the Earth. In fact, Tuscany is a literal hotbed for geothermal energy – even with its own geothermal museum!

A room with a view – Our room, in Pomarance, with a view to the geothermal power plants in Larderello.

To all girlfriends-of-geologists out there, I promise: I did not have back thoughts when we decided to go to Tuscany for summer vacation. The better half suggested Tuscany for a country-style-magazine vacation, wine, and the best. gelato. evvah!, and I did not see any reason to object. We choose Pomarance, a very Italian small town with a pittoresque square, gelateria and a pizzeria that fills up in the evening. On the hill tops next door: the über-cozy-medieval-castle-on-a-hill tourist-towns of Volterra and San Gimignano.

And, a pure coincidence, the next village in the other direction is Larderello, the cradle of geothermal energy. Well, being there, a geologist cannot resist the urge to have a look, and draw in the lovely smell of sulphur in the morning, the smell of hot springs, now tamed by engineers.

Francois de Larderel on his pedestal in front of the geothermal museum. They built more monumental those days!

Already the old romans knew the hot springs, and used them for bathing. Much later, it was discovered that the water coming up from the ground contains boric acid, and in 1827 the Frenchman Francois de Larderel found how to extract it.

First, the brine was boiled on wood stoves to dry out the salts, but the need for firewood hit hard on the woods around. Then came the idea to build built brick domes right on top of the mudpots, to extract the salts by the heat itself. They looked quite like igloos, and became the logo of the Larderel company. A company town grew up and got the name of the company founder. For some time, Larderello boomed on the salts from beneath.

But how long was Adam in the hot spring paradise? Everything is bigger in America, and when in the 1920s large mines started to exploit borax deposits in California, they pushed prices down and the Larderello boron industry out of business.

Luckily, by then, there was a new kid in town: Prince Piere Ginori Conti, a man of many talents, the drive to get projects through – and a matching ego. In 1904, Conti constructed the world’s first geothermal electric powerplant, by connecting a piston generator to steam coming out from the ground.

It lit three light bulbs.

From there, drills rapidly went down and technology took off, and the first commercial power plant opened in 1911. It was a quite simple construction; steam from the ground drove the generator, then it went into the cooling tower – built of wood! – and, as water, back into the ground.

Just like in the oil industry, the times have changed. The iconic wooden derricks going more-or-less straight down have given way to automated rigs and directional well drilling, right along the fracture zones which bring the hot water to the surface.

From the well sites, pipelines crisscross the landscape like big metal blank worms in a sci-fi movie, and bring the hot steam or water to the power plants.

Modern steam plants – a.k.a.flash steam plants – handle very hot steam steam, up to 180 C. Coming up from high pressure at several kilometers depth, it starts out as water, but on the way up, it separates into vapour and water. The steam powers the generator, while the water – together with the water condensed in cooling towers – goes back into the ground.

On the slightly colder side are warm-water generators – a.k.a. binary cycle generators. The water goes into a heat exchanger and heats a fluid with a boiling point much lower than water, and that steam drives the turbine. They make it possible to produce electricity outside the hottest spots, from water down to 57 C, but also serve as secondary generators, to use the condensed water and remaining heat in the cooling water in flash plants – a.k.a. double cycle plants.

The power plants in Tuscany comprise all of these types, as they were built at various times and stages of technology. Today, nearly all new plants are double cycle, and older plants gradually get replaced by new and more efficient.

But Mother Nature cannot give away unlimited energy. Pump too much water out, and the wells run dry. Most geothermal power plants therefore pump water down into the ground again, but then run the risk of cooling down the rocks down there. It is a delicate balance to get the max out of the ground, without destroying the long term heat supply.

Why Tuscany? Everybody knows Iceland is volcano country, but Tuscany, isn’t that a bit away from famous Etna and Vesuv?

As even a muggle knows, the African plate pushes into Europe and creates a big mess, including the tall Alps and the mountains in the Balkans. Today, the Mediterranean sea crust plunges beneath Sicily, but then stretches up as a finger into the Adriatic sea, and plunges beneath Italy from the east side. Down there, the subdued crust heats up, melts and floats to the surface, where it emerges as volcanoes. Vesuvius and Etna are the most famous, but are only two of many volcanoes and hot areas on the boot of Italy.

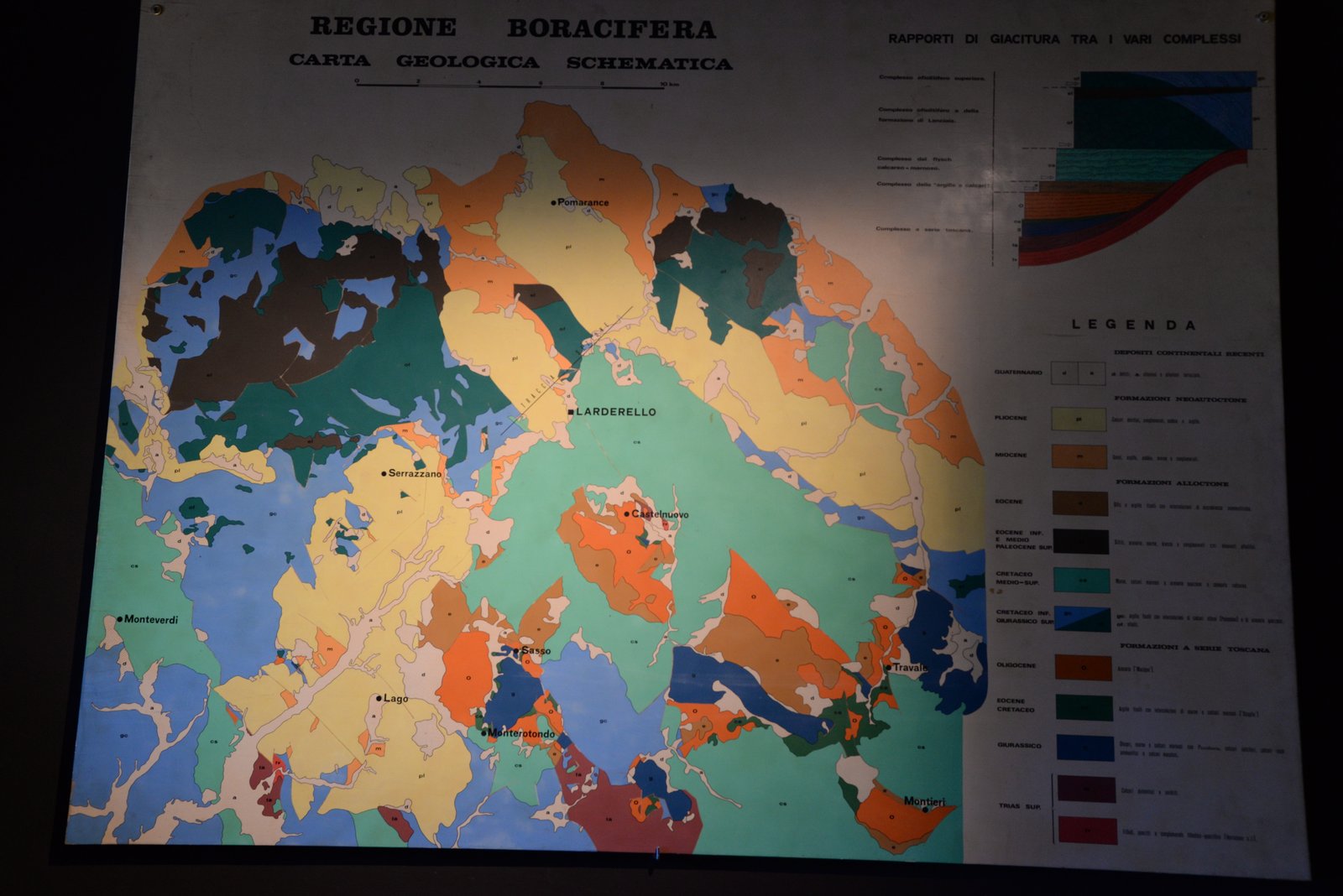

Geological map of Larderello and surroundings. I get that the rocks of the area mostly are severely stacked and faulted Jurassic and Triassic,sedimens, with a Cenozoic blanket on top. Otherwise, I did not have time to get complete control on the tectonostratigraphy…

Some of the ascending rock blobs do not reach the surface, but remain just below as hot balls of granite. Such are the sources of the heat in Tuscany, where the steam and water ascends through faults and fractures, through the stacked and twisted mash of metamorphic rocks and limestones that make up the surface.

Here, the hot water of Tuscany produces around 770 megawatts, 26% of the electricity consumption in Tuscany, and nearly 2% of Italy’s. Many towns, our own Pomarance also gets their hot water from the geothermal plants.