El Teide is at 3718 meters not only the tallest mountain in Spain, but the third tallest mountain in the world – measured from its base at the seafloor, that is. Only the Hawaiian twins Mauna Loa and Mauna Kea are taller. As you know, Teide’s characteristic dome cone is also one of my favourite geo-places.

But, the present Teide is, actually, the second and smaller volcano on Tenerife. Around two hundred thousand years ago, an even taller cone towered above the island, scaring lizards and canary birds. It might well have been more that four kilometers high. No people had yet arrived on the Canary Islands, and that was just as well, for this volcano would not last. The whole thing collapsed, the west side of Tenerife slid into the sea, and the volcano sunk into a a nine by 16 kilometers wide depression: The Las Canadas Caldera.

Since then, the Teide of today has steadily grown from the base of the caldera. In the religion of the native Canarians, the Guanches, Teide was the prison of Guyaota, the devil. Eruptions happened when the devil fought to try to get free. Guyaota must have fought hard, for Teide was regularly active when the white man came to the islands. Christopher Columbus described seeing a mountain on fire, when the Canaries was his last stop before the Atlantic, on his journey to stumble upon America. In 1706, a lava stream drowned half of the port town of Garachico. The last eruption from Teide itself was in 1798, from the shoulder summit Pico Viejo. The lava streams from this eruption lie like thick, black snakes on the older, brown mountain side. The last eruption on Tenerife was as late as in 1909, from the Chinyero fissure, west on the island.

If a volcano explodes and no guanches are there to hear it, did it really happen? How do we know that the volcano exploded and collapsed? Because of the caldera, the big crater. Caldera is Spanish for cauldron, and the rims of the cauldron are the former flanks of the really big volcano.

Las Canadas is a world of its own. You cannot see it from the lower parts of Tenerife. On distance, the crater rim looks just like an irregular step on the way up to the mountain, clad in dark green pine forests. Only when the winding road climbs over the rim at two km altitude, the panorama reveals: A desert world in red, brown and black, with bizarre patterns and twisted lava flows. A place where the only signs of life are brushes and cactuses, and where the cowboys and redskins could chase each other across the burned soil.

In real life, the Las Canadas desert is today full of tourists, and even has a Parador luxury hotel. The muggle tourists come to go to the top of Teide, and to admire all the bizarre, colorful rocks. Through geology glasses, the rocks also tell the story of the Las Canadas caldera.

We start early in the morning. The caldera is still dark, and the sun merely shines its first rays on Teide’s peak. From the dark, the mountain emerges as a pattern of earth colors; white, grey, brown and black. They are lava streams and ash, the color varying by age and composition.

The rim of Las Canadas, built up by layers of ash and lava on the flank of the mighty volcano, which stood here before Teide. The vertical stripes are dikes, late intrusions of which spread out around the axis of the volcano, and cut through the older layers.

Sun rises fast here at low latitude, and soon bathes the wild west landscape in all its rustique, brutal glory. The caldera looks like Tatooine. The crater walls reveal layers upon layers of lava. These are the flanks of the mighty volcano, which once stood in Teide’s place. In between the lava layers are light pods of ash, which once fell into gulleys in between the lava flows, or into deep cracks. Vertical, dark bands cut through it all. These are dikes of magma, which spread out from the centre inside the volcano, and towards its flanks.

The chocolate pudding glacier: A flow of lava, which flowed from Teide’s flank and down to the caldera floor. It stopped just before a wall of rocks; the remnants of a dike. The building in the background is the Parador hotel.

Some plants have adapted to the desert. Low brushes with lichen green color dot the ground. Life always finds a way, even where almost no water exists.

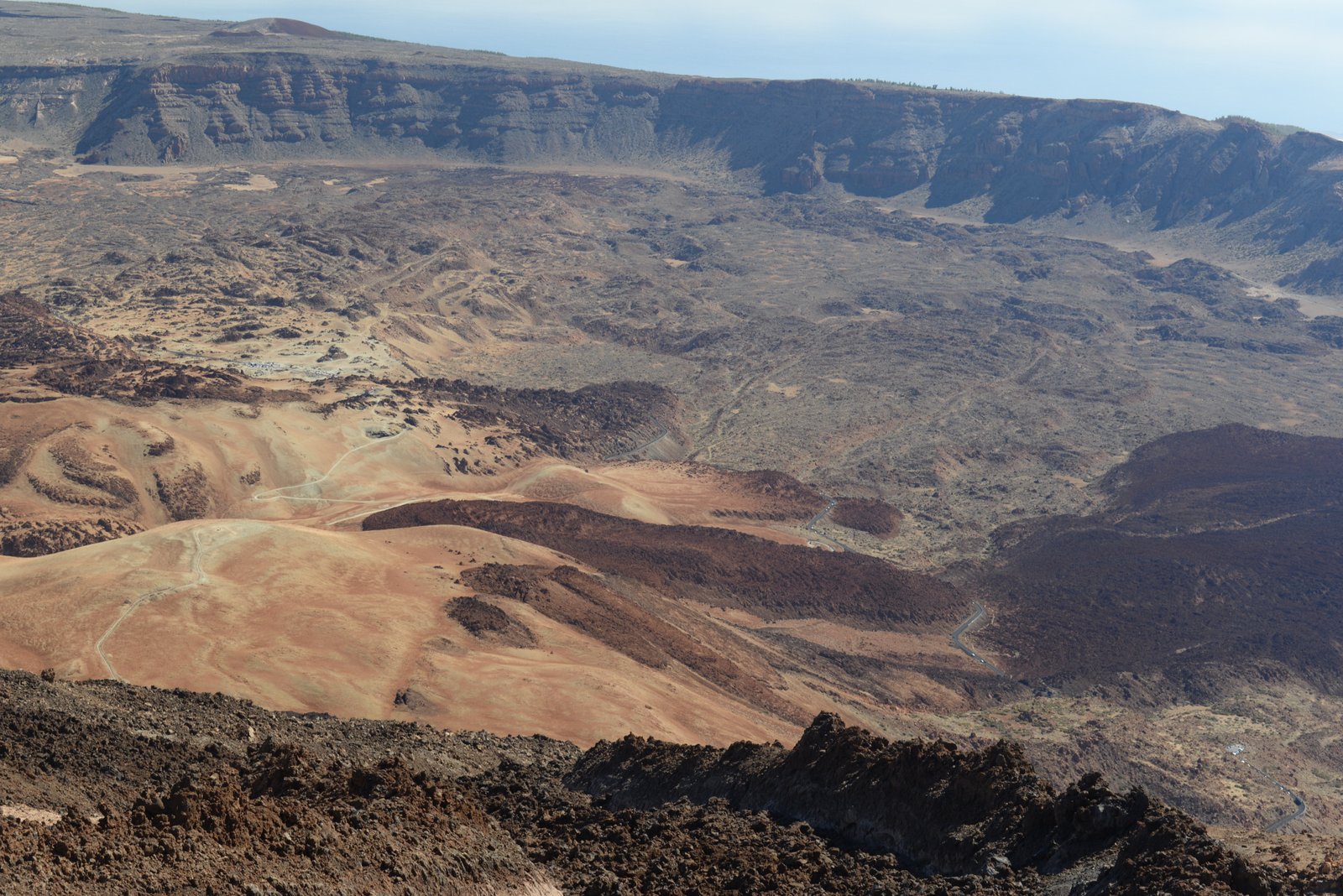

The best view of Las Canadas is of course from the top of Teide itself. Large fans of old, brown ash lie on its flanks, as if some giant kid had thrown a heap of brown sand down from the top. Then there are the dark brown and black flows of lava, floating down as a big slush pile of chocolate pudding. One large flow looks like black glacier, which stops just in front of a wall of rocks – the remnants of a dike, which once came up through the crater floor, and since has withstood erosion.

Looking down at Las Canadas from near the top of Teide shows the large dimensions. Two hundre thousand years ago, a volcano taller than Teide covered it all.

In the horizon, the rim stands like a fortress wall in the horizon, with layers of lava from the volcano which once stood here. Teide v.1 thus was bigger, wider and probably taller than Teide v.2 of today.

How to get there

Tenerife is the largest of the Canary Islands, and is connected to most major European cities by a wide array of both regular and charter flights. Especially the low-fare airlines fly often to this island in the sun. Many charter operators also offer “flights only” tickets, but this usually restricts the stay to one or two weeks.

Tenerife has two airports, North and South. Most international flights arrive at the south airport, while the north airport is mostly for domestic Spanish flights.

I strongy recommend to rent a car to get around. Car rental is very reasonable, starting at around €200/$250/£170 per week (depending on size and season). Tenerife also has a very well developed bus network, but the buses to Teide runs only a few times per day.

To get from the south airport to Las Canadas, drive from the airport westwards on the TF-1 highway, then follow the narrow and winding TF-657 and TF563 up to the rim of the caldera, where it meets TF-38. The road to Teide is well shown by road signs. If the narrow road feels scary, follow TF-1 along the Adeje coast towards Santiago, and just before Santiago, follow TF-38 in a long slope along the mountain. TF-38 also takes you past the Chinyero lavas from the last eruption on Tenerife in 1909.

I really wanted to see it when I went to Tenerife in march I took my son because it was his 21st birthday but after 3 days the island was put under lockdown but I hope to return next year.

Hi Karsten

I’m doing a talk on volcanoes I’ve visited and came across your piece – it’s great! Really interesting and informative, and I like the conversational tone. I have an almost identical photo of the caldera from the top of Teide, amazing views.

One small point, I think the eruption may have been in 1798 (not 1789)?

All the best

Thanks for the kind words, and for pointing out the typo, Liz! :)