I am a Norwegian, and I confess to not have gone to the mountains this Easter. This might get me expelled from community of True Norwegians, but me and the better half have fallen in love with that flat country of hygge & smørrebrød just to the south, so we went there to meet the spring. Winter, we have already had enough of that! (And, the Danes have more chocolate!).

Instead, we headed for Århus, Denmark’s second largest city. Århus has quite an art scene, including the Aros museum of contemporary art and its rainbow panorama, which fits my art interested lady perfectly. For me, there was the geology.

I went hunting for Easter Eggs. Many years ago, on a trip with my mom and sister, when they enjoyed the picturesque streets of Ebeltoft, I took the car and raced around on the Mols Peninsula, to a klint, the danish word for a chalk cliff, where I had found some fossil sea urchins. The fossils had been scrapped in one of those trash-first-think-later cleanouts, and I wanted to find the klint again – and hopefully find some of the limestone eggs, the remnants of life in a 64 million years old sea.

The cliff at Sangstrup. Note the messy appearance; this was no calm sea! The sea urchin fossils sit in the white band around hafway from the base.

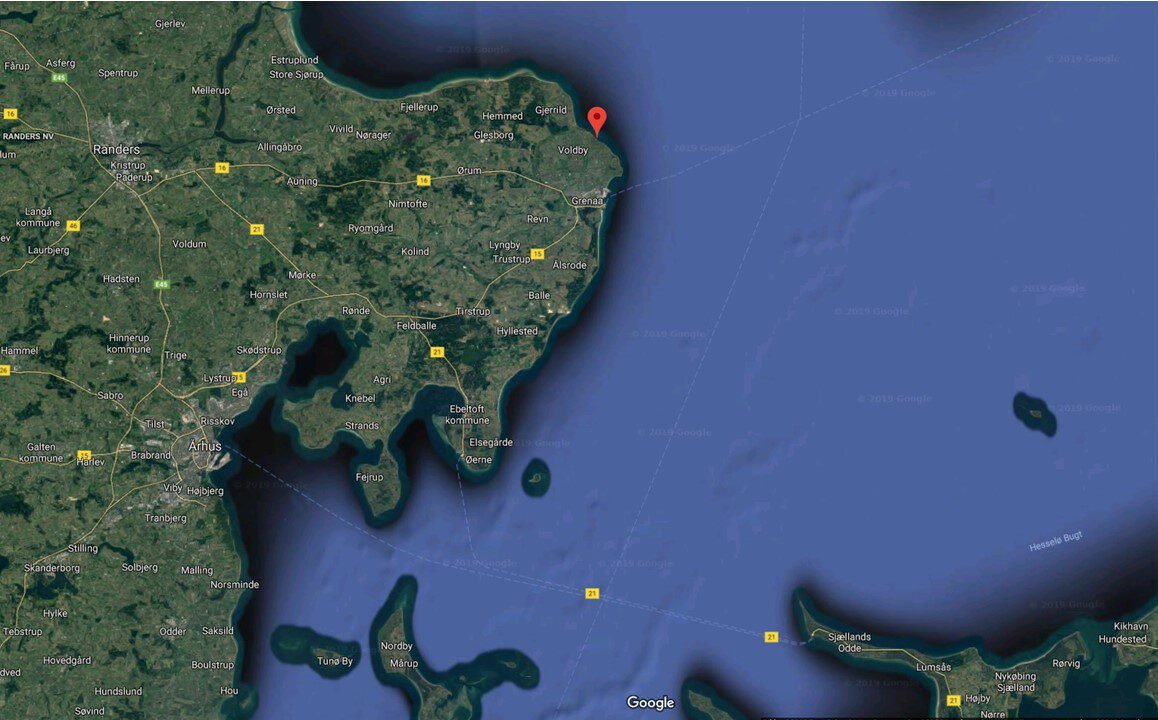

We found it. Sangstrup Klint, at the end of a small road just north of Grenå, on the eastern end of the Mols Peninsula. There was the beach, very typical of Danish beaches in geology of this age: It is mostly pebbles of flint, left behind after the sea has ground the surrounding limestone to powder and washed it away. And there was the cliff, with dark spots of flint in place. Flint is really a kind of silica, amorphous quarza, which fills in cavities in the ground, which in turn are burials made by creepy-crawlies that lived in the sediments when they were soft.

And there were the sea urchins, my Easter Eggs. Blobs in the yelowish chalk, which may require a second look to be distingushed. I didn’t bring any hammer or chisel, it would probably not be well received, but with some dirt on my fingers, the fossils came ut. Not the prettiest of fossils, or scientifically important, but a good memory from a fine trip.

These sea urchins lived around 64 million years ago, in geological terms just after the dinosaurs said good night. Life had conquered the oceans once more. Sea urchins are the most common fossils at Sangstrup, but there are also crabs, sea stars and the occasional shark tooth to be found.

They lived in a shallow sea where tiny algae produced large amounts of fine chalk. The rock at Sangstrup is a chalk stone, and is really made up of zillions of tiny pieces from these microorganisms. The sea was shallow, but not calm; waves and curents shuffled the chalk around before it finally settled, and that is why the rock looks so messy. It is messy. The fossil sea urchins are actually not the shells themselves, but casts, made by chalk, which filled in the inside, after the organic material had rotted away.

This chalk covered the whole of Denmark at the time. In fact, this very first part of the Tertiary, the «third period» (after the dinosaurs in the Mesozoic, the Middle period) is called the Danian in official geology terminology. Later, Denmark was tilted so the Danian chalk appears in a band from northwest to southeast. Today the geology is covered by agriculture and towns, and the coastlines are the best places to see the chalk. Like at Stevns Klint, where the dinosaurs died, and at the shlighly younger Sangstrup Klint.

How To Get There

Sangstrup Klint is around 5 km north of Grenå, which is the easternmost town in Jutland – it sits on “the nose” of Jutland. Grenå has a ferry connection (Stena Line) to Varberg in Sweden. From Århus, the driving distance is ca 65 km along route 35 to Grenå; from there follow the smaller roads to the tiny village Sangstrup, and to the cliff. Århus Airport has services from Copenhagen, Stockholm, London, Oslo, Berlin and Munich (among others) and is situated on the road between Århus and Grenå. It is also possible to rent a car in e.g. Copenhagen and take the express ferry from Sjællands Odde to Ebeltoft.

This post is partly based on the book Geologiske naturperler – danske brikker til Jordens puslespil (Geological nature pearls – Danish pieces to the Earth puzzle) edited by Bent Lindow and Johannes Krüger.