Denmark is the cosy little country, with klitter, klinter and kanelsnegler – sand ridges, sea cliffs and cinnamon buns. But det søde, bløde land – the sweet, soft country, shrinks a bit each year, and Norway is partly to blame for that.

We packed the car full of baby, baby gear and camera gear, and hit the ferry and road to Lønstrup, a cosy village with cafees, craftspeople and summer cabins, just southwest of the port of Hirtshals. But a hidden menace threatens Lønstrup: The ocean comes closer to the town every year. Not only there, but along large parts of the coast of north Jutland, two-three meters of the coast falls into the North Sea every year. The sweet, soft country falls prey to the eternal hammering of the waves exactly because it is soft.

This farm lives dangerously. In ten-fifteen years, the beach will likely eat the white houses.

The landscape on northern Jutland has been shaped by more than two million years of ice ages, What we often call “the ice age” was not a single event, but a long string of cold spells, where the glaciers reached all the way across Denmark and even into Germany, relaying with warmer periods, when the ice retreated. Lønstrup sits on sediments, which are from 34 000 to 14 000 years old. They vary between moraines from the glacier fronts, sediments from the shallow sea, from rivers and from big lakes, which where dammed by the ice itself, before they burst and the water flowed out and across Denmark, bring sand with it.

Rubjerg Fyr, the abandoned lighthouse in the middle of a sea of sand that it helped create, blown up from the beach below, as the beach ate its way towards the lighthouse. Ghosts are optional.

The glaciers and their load came from the Scandinavian bedrock, north and east of Denmark. Much of the sand that makes Denmarks soft comes from this Scandinavian basement, ground out from what would become valleys and fjords, before it rested between Skagerak and Kattegat. The sand would not rest undisturbed. Later glacier advances had such a power that they thrusted sheets of the sand up into stacks and bent it into folds, like the snow in front of a showel.

Jutland is famous for its fantastic beaches, which stretch along the west and north coast, created by sand washed onshore by the waves. But where the coast behind the beach is high, it is also vulnerable. Winter storms with their high waves dig in and create the steep cliffs, the klinter, which slowly eat their way into the land.

A klitte in the making: The beach grass captures the sand, and the dune grows, later to become a ridge along the coast.

The wind always blows on the west coast of Jutland, the same wind that powers the waves from northwest. The wind grabs sand on the beaches, lifts it up and carries in over the land. When the wind then meets vegetation, loose sand or topography, which makes it loose some of its energy, it can no longer carry the sand, and leaves it behind, usually as a belt just inside the coast. These first sand dunes then grow as more sand is dumped on their lee side, creating klitterne, the characteristic Danish landscape with sand ridges between the shore and the low land behind.

No, not the border of Sahara. But the wandering sand dune at Rubjerg is as big as desert dunes.

Enough sand and the right wind can also build vandreklitter, large wandering sand dunes, which move across the land. This flight of sand, sandflugten, was previously a big problem. Many farmers saw both houses and fields drown beneath the sand, as in a desert. It was not before the mid of the nineteenth century the Danes got the sand flight under control, after a huge effort of forest planting. Ironically, the sand flight, which started in the sixteenth century, probably happened largely because forests had been cut down for firewood and building war sailing ships, exposing sand for the wind.

Rubjerg Fyr – fyr meaning lighthouse – near Lønstrup, sits right inside one of the last remaining of the large wandering dunes – the lighthouse is actually one of the reasons the dune is so big.

Rubjerg Fyr was opened in 1900, two hundred meters in and sixty meters up from the sea, on the highest point of the Rubjerg Klint cliff. But sand blowing up from the beach hampered the lighthouse from the start. The sand filled the water well and the kitchen gardens. With the sea approaching, the problem grew, the houses started to drown the sand. In a desperate attempt to stop the sand, the the growing sand ridge in front of the lighthouse was planted with European beach grass, but this only caught more sand. The sand ridge grew so tall that it blocked the light from the lighthouse in some directions. Rubjerg Fyr was shut off for the last time in 1968.

Rubjerg Fyr and the large sand dune seen from the land side. Note the small people for scale!

But the coast never rests. The cliff edge continued to eat its way inwards, and with it, the big sand dune has continued its slow wandering. Today, most of it is inside the lighthouse. And that even though the lighthouse itself has moved, to not fall into the sea.

Rubjerg lighthouse may be dark, but it is still a landmark, both physically and in the soul of the Danes. To protect it, they moved the whole thing away from the edge in October last year, by digging down to the sole, placing it on solid rails, and pulling 70 meters inwards. Then it will stand for some more decades.

Two evenings, I went out to the lighthouse. The wind was gale, with sand everywhere and in the air. Forget any thought of changing lenses on the camera. Even with a tripod, the wind hugged the camera, so I just had to fire the camera, “spray and pray”, and hope some images came out sharp. But with the sun god Ra on the way towards his rest in the west, the light was in an ad for VisitDenmark, and the flying sand painted abstract pictures in the air and on the ground.

One rainy morning, I also drove out to where Mårup Church once stood. Mårup Church was built in the thirteenth century, at that time two kilometers from the sea. But today, only half of the churchyard is left. The rest has fallen down, occasionally people find skulls on the beach. The church itself was torn down in 2015, before the sea did. Archeologists did their work, but I find it close to cultural vandalism that the church ended as road fill, instead of the original plan of restoring it another place.

The church yard and parking place at what was once Mårup Church, now half eaten by the sea.

Klitter and klinter, soft and hard, cosy hygge and wild nature near the ocean. So similar to home, and yet so different, not the least the geology. These contrasts are what I love about Denmark, and have made a trip there a tradition each spring, to celebrate the return of warmth and light. This year, that virus delayed our trip to the fall. When it is all over, we will come back to you, little country!

“Driving allowed only with a special permit”.

Lønstrup’s location on north Jutland. The nearest international airport is Aalborg and the nearest railway station in Hjørring. Bus no 80 connects Hjørring with Lønstrup, but the best way to get around is by car. From the south; E45 to Aalborg and E39 to Hjørring, then follow signs westwards to Lønstrup – or follow road 55 from Aalborg through the Danish countryside. From Hirtshals; road 55 and then signs westwards; from Frederikshavn road 35 to Hjørring and then road 55. Both Hirtshals and Frederikshavn have rail connections to Hjørring and Aalborg.

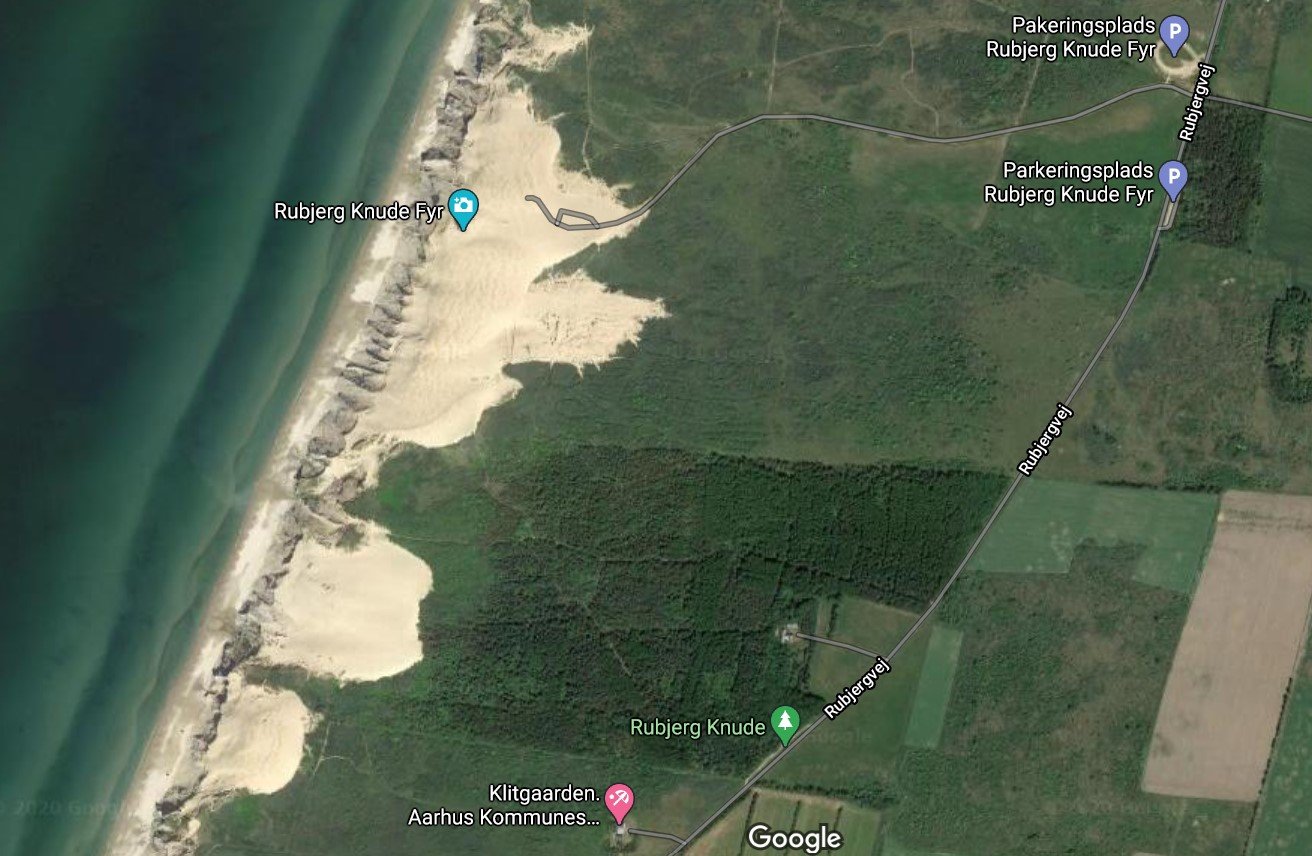

Rubjerg Fyr and the big sand dunes from above. Note how the sand dunes today have progressed inwards from the lighthouse. Car parking at the parking space in the upper right corner, then follow the gravel road to the dunes and the lighthouse.

Mårup Church is still on Google Maps…but where it once stood is now in the air, on the wrong side of the cliff. Comparison to the image here shows how severe the coast erosion has been.

This post is based partly on the book Naturen i Danmark – Geologien (chief editor: Gunnar Larsen), which gives a comprehensive overview of Danish geology from the Precambrian to the recent.